by Merryana Salem

The Measure Of A Hero Is Sometimes Hobbit-sized.

In a world inundated with flawed angst ridden Captain America, Supermans and Professor Xaviers, it can be tough to find an actual everyday hero. I don’t know about you, but all these superhuman/enhanced/highly trained heroes blowing up things for our entertainment can make one feel that the everyday average bachelor is an inadequate candidate for the title of hero. But what if we were given such a hero a long time ago?

One of the many things all heroes from all genres share is some kind of journey. “The Hero’s Journey” is a pattern of narrative identified by the American scholar Joseph Campbell that appears in drama, storytelling, myth, religious ritual, and psychological development. Briefly summarised, the stages of the hero’s journey is as follows: The ordinary world, the call to adventure, refusal of the call, meeting with the mentor, crossing the threshold, tests, allies and enemies, approach, the ordeal, the reward, the road back, the resurrection and return with the elixir. Bilbo Baggins’s journey in “The Hobbit” very much adheres to this most basic hero’s journey structure with only a few minor differences in arrangement. But does taking the hero’s journey automatically make him hero? Or, like our angsty action stars, must he prove himself?

Tolkien almost tells us to do away with the stereotype of the hero at the beginning of “The Hobbit” when Gandalf states that he “sought a mighty warrior, even a hero… [But] warriors are busy fighting one another in distant lands, and in this neighbourhood heroes are hard to come by.” A statement that can almost be argued as Tolkien showing his disregard for the idea of the warrior hero we are so used to, even today.

But Tolkien was greatly influenced by the old heroic texts such as Beowulf and The Hobbit attempted to re-write the hero as a figure less impossibly powerful for the modern age. However, Bilbo’s initial motives to partake in the quest are typical of old heroics. Like the heroes of old, Bilbo seeks to prove himself the Burglar, that Gandalf claims him to be, stating in the first chapter that, “He suddenly thought he would go without bed and breakfast to be thought fierce!” With the desire to prove himself, the promise of one fourteenth of the treasure and the danger of certain death, Bilbo’s journey’s beginnings has all the classic motives for heroic action.

However, it can be argued that Bilbo is merely the vessel through which the audience vicariously takes the journey to the Mountain. We only ever read events from his point of view and as a small hobbit and the last addition to a company already 13 strong, Bilbo is hardly painted as the typical lone wolf masculine hero, with the company commenting he, “looks more like a grocer than a Burglar.” It is in fact Thorin Oakenshield, Tolkien paints with the brush of our more typical fantasy hero. With the weight of a great destiny on his shoulders, his quest to attain his homeland and his leadership upon which the company depends for unity, Thorin appears to be the true hero while Bilbo is just along for the ride. Yet, for almost 100 years, the audience has perceived Bilbo as the “hero”, despite being surrounded by figures far more fitting to the conventions of the role then himself. So, why then do we perceive him as such?

I believe the answer is that Bilbo is the everyman. His characterisation is made up of commonalities shared by the middle class single man and offers a sharp contrast to the unattainable prophesied action archetype typical of the genre i.e. Beowulf, or Conan, or even Captain America. When declining Gandalf’s proposal of adventure, Bilbo replies that adventures are, “nasty disturbing uncomfortable things! Make you late for dinner!” Where most other heroes of the genre typically decline the invitation due to the obligations of normalcy, Bilbo’s refusal comes from a willingness to remain comfortable. Tolkien gives Bilbo the same values as an “ordinary” human being and so we perceive him as one of us (I don’t know about you, but I would much rather face a warm cup of tea than a menacing fire breathing dragon any day!). This in combination with our perspective being limited to Bilbo’s ensures through empathy that we perceive him as the most important character, if not the hero.

But as we progress further in the narrative with Bilbo as our eyes and ears, he laments leaving and longs for home, ‘”Bother burgling and everything to do with it! I wish I was at home in my nice hole by the fire, with the kettle just beginning to sing!’ It was not the last time that he wished that…” Just like you or I, Bilbo values home above all else. But it is this value for homely comforts that drives him to assist the dwarves in reclaiming theirs. Where heroes of old were defined by great acts of physical strength that borders on the superhuman, Bilbo is defined by his physical courage and altruistic reasons that stretch beyond glory, fame and fortune. But Bilbo receives praise equal to the warrior heroes his character subverts, “You are more worthy to wear the armour of elven princes than many that have looked more comely in it.” This is what Bilbo’s role as our “hero” comes down to. Bilbo’s unwavering loyalty to the concept of “home” is what gets the company to their destination because Bilbo’s loyalty lies with no single person, or promise of Gold, he keeps his eye set on the goal of getting the dwarves home and he achieves it. Yes, without Thorin the company would have no leader, but maybe that’s the point.

Ultimately, Tolkien dispels with the idea that the fantasy story must only herald a single hero and possibly even implies that the strong, burdened hero is too self-absorbed in his pursuit of fortune and fame to finish his quest alone, because it is only by the actions of all characters that the homeland is reclaimed. Even in “Lord Of The Rings”, despite the fact that the fellowship is dismantled, Frodo and Sam could never have destroyed the ring without them, or even Gollum.

Finally, the point repeatedly made throughout this essay is that Bilbo is a sharp contrast to the typical masculine hero. His fussing over hankies, dishes, doilies and discomfort give him stereotypical feminine qualities, despite Tolkien labelling him as male. Bilbo has next to none of the qualities of the typical male hero. He is small, non-threatening and has no special skills in combat. His skills lay mostly in keeping the household, a role stereotypically reserved for a woman. Tolkien, through Bilbo, dismisses the toxic masculinity trope that usually comes hand in hand with the idea of the hero in fantasy, even going so far as to say that Bilbo’s knack for adventure is inherited from his mother Belladonna Took. Tolkien attempts to dismantle the idea that heroism and weakness are only associated with certain gender stereotypes, and that masculinity does not equal strength or heroism.

The role of the hero is vast and varied, depending upon the genre into which they reside. But the job of any hero is to guide us morally through a world that reflects aspects of our own. Bilbo Baggins is an ordinary man tossed into an adventure that threatens his life and seeks to test his resolve at every turn, but Bilbo remains unchanged morally and it is this quality that makes him a hero. It is Bilbo’s loyalty and courage to act that makes up for the more stereotypically masculine heroic qualities he lacks, and keeps his motives truly altruistic. Bilbo is the non-stereotypical heroic figure in a stereotypical hero narrative, but a hero no less. We live in a world where ordinary has become inadequate owing to the superhuman superheroes Hollywood throws in our faces. It’s no wonder so many of us feel our averageness isn’t action hero worthy when being ordinary (paying bills, being kind, being positive, working hard) can be 10 times harder than facing trolls. But the next time you feel too everyday for hero status, remember that Bilbo Baggins, a man who insisted the company turn back because he forgot his handkerchief, outsmarted a fire breathing dragon by sucking up to it while all the warriors waited outside.

Merryana Salem is a 22 year old Lebanese/Australian with a PHD in procrastination, contently daydreaming at the edge of the world. She writes stories about the worlds in her head and the fears in her heart and probably should be studying right now. But most of all, she is thankful that you came here to read something she wrote.

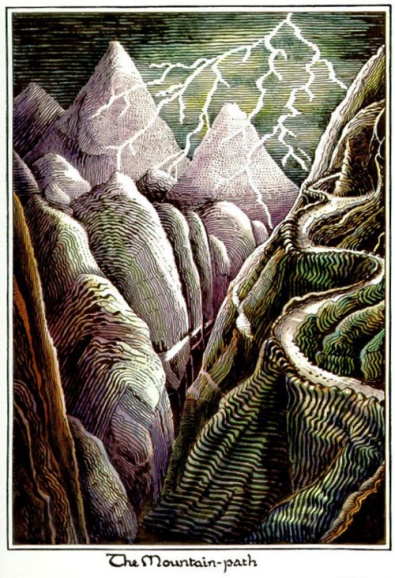

Illustration by J.R.R Tolkien